6:1 Those who are under the yoke as slaves must regard their own masters as deserving of full respect. This will prevent the name of God and Christian teaching from being discredited. 6:2 But those who have believing masters must not show them less respect because they are brothers. Instead they are to serve all the more, because those who benefit from their service are believers and dearly loved.

It is clear that there were many slaves and masters in the churches of NT times (cf. Philemon; 1 Cor 7:21; Eph 6:5-9; Col 3:22-4:1; 1 Tim 6:1-2; also 1 Pet 2:18-21.

William Barclay comments on why the early Church did not seek the sudden abolition of slavery:

‘There were something like 60,000,000 slaves in the Roman Empire. Simply because of their numbers they were always regarded as potential enemies. If ever there was a slave revolt it was put down with merciless force, because the Roman Empire could not afford to allow the slaves to rise. If a slave ran away and was caught, he was either executed or branded on the forehead with the letter F, which stood for fugitivus, which means runaway. There was indeed a Roman law which stated that if a master was murdered all his slaves could be examined under torture, and could indeed be put to death in a body. E. K. Simpson wisely writes: “Christianity’s spiritual campaign would have been fatally compromised by stirring the smouldering embers of class-hatred into a devouring flame, or opening an asylum for runaway slaves in its bosom.”

‘For the Church to have encouraged slaves to revolt against their masters would have been fatal. It would simply have caused civil war, mass murder, and the complete discredit of the Church. What happened was that as the centuries went on Christianity so permeated civilization that in the end the slaves were freed voluntarily and not by force. Here is a tremendous lesson. It is the proof that neither men nor the world nor society can be reformed by force and by legislation. The reform must come through the slow penetration of the Spirit of Christ into the human situation. Things have to happen in God’s time, not in ours. In the end the slow way is the sure way, and the way of violence always defeats itself.’ (DSB)

On the other hand, writes Bartlett:

‘When both master and slave were converted to Christ, they became equals and brothers (Gal. 3:28). This brotherhood became such a powerful new reality in Christian communities that Paul had to remind slaves who had Christian masters not to be disrespectful to them, as being brothers (1 Tim. 6:1–2).’ (Men and Women in Christ)

So that God’s name and our teaching may not be slandered – Failure to live as Christians in any department of our lives brings God’s character and the gospel into disrepute.

Christian faith does not erase social responsibility:

‘It is a continual danger that a man may unconsciously regard his Christianity as an excuse for slackness and inefficiency. Because he and his master are both Christians, he may expect to be treated with special consideration. But the fact that both master and man are Christian does not release the employee from doing a good day’s work and earning his wage. The Christian is under the same obligation to submit to discipline and to earn his pay as any other man.’ (DSB)

Don’t use your new-found freedom in Christ as an excuse for sloppy or disrespectful behaviour.

Summary of Timothy’s Duties, 2b-19

Teach them and exhort them about these things. 6:3 If someone spreads false teachings and does not agree with sound words (that is, those of our Lord Jesus Christ) and with the teaching that accords with godliness, 6:4 he is conceited and understands nothing, but has an unhealthy interest in controversies and verbal disputes. This gives rise to envy, dissension, slanders, evil suspicions, 6:5 and constant bickering by people corrupted in their minds and deprived of the truth, who suppose that godliness is a way of making a profit.

‘The apostle evaluates the false teachers in relation to questions of truth, unity and motivation. His criticism of them is that they deviate from the faith, split the church, and love money. They are heterodox, divisive and covetous.’ (Stott)

False teachers have been at the back of Paul’s mind throughout this letter. There is an assumption here that ‘false doctrines’ and ‘sound instruction’ can be defined and distinguished. There is a standard of belief which he calls the ‘teaching’, v1, 3; ‘sound instruction’, v3, ‘the truth’, v5; ‘the faith’, vv10, 12, 21, the ‘command’, v14, and ‘what has been entrusted’, v20. The false teachers have departed from this norm.

Note how Paul characterises orthodox teaching:

(a) It consists of the sound instruction (lit. ‘the sound words’) of our Lord Jesus Christ. Paul regarded his teaching as that of Christ, cf. Lk 10:16 Acts 1:1 2 Co 13:3. ‘The exalted Christ is both the ultimate source of the apostles’ doctrine and the great subject of all their preaching’ (Wilson).

(b) It is godly teaching; it accords with and leads to godliness.

‘Observe, The doctrine of our Lord Jesus is a doctrine according to godliness; it has a direct tendency to make people godly.’ (MHC)

“It is an undoubted truth that every doctrine that comes from God, leads to God; and that which doth not tend to promote holiness is not of God.” (George Whitefield)

‘When men are not content with the words of the Lord Jesus Christ, and the doctrine which is according to godliness, but will frame notions of their own and impose them, and that too in their own words, which man’s wisdom teaches, and not in the words which the Holy Ghost teaches, (1Co 2:13) they sow the seeds of all mischief in the church.’ (MHC)

‘The words of our Lord Jesus Christ are wholesome words, they are the fittest to prevent or heal the church’s wounds, as well as to heal a wounded conscience; for Christ has the tongue of the learned, to speak a word in season to him that is weary, Isa 50:4. The words of Christ are the best to prevent ruptures in the church; for none who profess faith in him will dispute the aptness or authority of his words who is their Lord and teacher, and it has never gone well with the church since the words of men have claimed a regard equal to his words, and in some cases a much greater.’ (MHC)

Cf. Isa 8:20.

This emphasis on normative belief can be contrasted which much that passes for ‘spirituality’ in our day:

‘”Spirituality” is, of course, one of the buzz words of our time, and can be taken to mean almost anything. I was at a party recently and got talking to a woman who told me she had given up her childhood Roman Catholic faith and was now “constructing her own spirituality,” something that apparently involved having an affair with a married man.’ (CEN, 2/6/00, p15)

Here is Paul’s description of the false teacher, what Lenski calls the ‘psychology of error’. He

(a) is conceited: his desire is not to display Christ, but himself;

(b) understands nothing;

(c) has an unhealthy interest in controversy;

(d) is evil in speech and attitude.

Note the inseparable connection between doctrine and behaviour. Unsound doctrine leads inevitably to immoral behaviour.

He is conceited and understands nothing – ‘The false teacher is inflated with the pride that blinds him to the truth, but though he knows nothing as it really is, he does not hesitate to confine the entire cosmos within the strait-jacket of his preconceived ideas.’ (Wilson)

‘The wit of heretics and schismatics will better serve them to devise a thousand shifts to elude the truth than their pride will suffer them once to yield and acknowledge it.’ (Trapp)

Quarrels about words – his concern is with the abstruse and the speculative. This letter contains a number of protests against needless controversies, 1 Tim 1:4; 4:3,7.

‘There is a kind of Christianity which is more concerned with argument than with life. To be a member of a discussion circle or a Bible study group and spend enjoyable hours in talk about doctrines does not necessarily make a Christian. J. S. Whale in his book Christian Doctrine has certain scathing things to say about this pleasant intellectualism: “We have as Valentine said of Thurio, ‘an exchequer of words, but no other treasure.’ Instead of putting off our shoes from our feet because the place whereon we stand is holy ground, we are taking nice photographs of the Burning Bush from suitable angles: we are chatting about theories of the Atonement with our feet on the mantelpiece, instead of kneeling down before the wounds of Christ.” As Luther had it: “He who merely studies the commandments of God (mandata Dei) is not greatly moved. But he who listens to God commanding (Deum mandantem), how can he fail to be terrified by majesty so great?” As Melanchthon had it: “To know Christ is not to speculate about the mode of his Incarnation, but to know his saving benefits.” Gregory of Nyssa drew a revealing picture of Constantinople in his day: “Constantinople is full of mechanics and slaves, who are all of them profound theologians, preaching in the shops and the streets. If you want a man to change a piece of silver, he informs you wherein the Son differs from the Father; if you ask the price of a loaf, you are told by way of reply that the Son is inferior to the Father; and if you enquire whether the bath is ready, the answer is that the Son is made out of nothing.” Subtle argumentation and glib theological statements do not make a Christian. That kind of thing may well be nothing other than a mode of escape from the challenge of Christian living.’ (DSB)

Such unhealthy controversies and petty quarrels between these false teachers lead to ‘a complete breakdown in human relationships’ (Stott). Five are mentioned: Envy is a resentment of other people’s gifts. Strife is a spirit of competitiveness and argumentativeness. Malicious talk bad-mouths rivals. Evil suspicions forget that fellowship is built on trustfulness. Constant friction (v5) is the inevitable fruit of intolerance and rivalry.

Constant friction – ‘The false teacher is a disturber of the peace. He is instinctively competitive; he is suspicious of all who differ from him; when he cannot win in an argument he hurls insults at his opponent’s theological position, and even at his character; in any argument the accent of his voice is bitterness and not love. He has never learned to speak the truth in love. The source of his bitterness is the exaltation of self; for his tendency is to regard any difference from or any criticism of his views as a personal insult.’ (DSB)

Who think that godliness is a means to financial gain – ‘The false teacher commercializes religion. He is out for profit. He looks on his teaching and preaching, not as a vocation, but as a career. One thing is certain-there is no place for careerists in the ministry of any Church. The Pastorals are quite clear that the labourer is worthy of his hire; but the motive of his work must be public service and not private gain. His passion is, not to get, but to spend and be spent in the service of Christ and of his fellow-men.’ (DSB)

And Paul will now develop this theme of ‘gain’. One thing is sure: the notion that godliness leads to financial gain is a fallacy; a lie.

‘The Greeks were intoxicated with the spoken word. Among them, if a man could speak, his fortune was made. It was against a background like that that the Church was growing up; and it is little wonder that this type of teacher invaded it. The Church gave him a new arena in which to exercise his meretricious gifts and to gain a tinsel prestige and a not unprofitable following.’ (DSB)

‘The history of the human race has regularly been stained by attempts to commercialise religion. It was when Simon Magus thought he could buy spiritual powers from the apostles that the term “simony” was coined, to denote the purchase and sale of spiritual privilege or ecclesiastical office. Paul himself found it necessary to declare that, unlike many, he did not peddle the Word of God for profit, that he had never coveted anybody’s silver, gold or clothing, and that he had never used religion as a cloak for greed. Yet the church was discredited during the Middle Ages on account of the disgraceful sale of indulgences; religious cults still charge exorbitant fees for personal tuition in their particular tenets; some evangelists appeal for “love offerings” which are never publicly audited; and some television preachers promise their viewers personal prosperity on condition that they send on enough “seed money”.’ (Stott) Cf. 2 Cor 2:17; Acts 20:33; 1 Th 2:5.

Here, in vv3-5, we have three tests that can be applied to all teaching: (a) is it consistent with the apostolic faith? (b) Does it tend to unite or divide the church? (c) Does it promote godliness with contentment, or covetousness? (Stott)

It has been said that Christianity is the worst trade, but the best calling, in the world.

6:6 Now godliness combined with contentment brings great profit. 6:7 For we have brought nothing into this world and so we cannot take a single thing out either. 6:8 But if we have food and shelter, we will be satisfied with that. 6:9 Those who long to be rich, however, stumble into temptation and a trap and many senseless and harmful desires that plunge people into ruin and destruction. 6:10 For the love of money is the root of all evils. Some people in reaching for it have strayed from the faith and stabbed themselves with many pains.

This statement echoes 4:8.

Note the arithmetic: Godliness + contentment = great gain.

Godliness – Cf. 1 Tim 2:2,10; 3:16; 4:7,8; 6:3,5,6,11; 2 Tim 3:5; Tit 1:1. This expression is only found elsewhere in the NT in 2Pe 1:3,6,7; 3:11). The contented ‘godliness’ that is enjoined here is in contrast to materialism (preoccupation with possessions), asceticism (an austerity that denies the good gifts of the Creator), and Pharisaism (placing on ourselves and others heavy burdens of rules). cf. Stott, New Issues Facing Christians Today, 280.

‘Godliness is glory in the seed, and glory is godliness in the flower.’ (Thomas Watson)

Contentment – The word is “autarkeia,” which ‘was one of the great watchwords of the Stoic philosophers. By it they meant a complete self-sufficiency. They meant a frame of mind which was completely independent of all outward things, and which carried the secret of happiness within itself.’ (DSB)

Godliness does lead to gain, but not the monetary gain the false teachers had set their hearts on.

‘Heb 13:15 summarizes the teaching in advising believers to be free of the love of money and to depend on God’s promise not to forsake his people. Food and lodging should be enough for the godly (1 Ti 6:6-10; compare Mt 6:34; contrast Lk 12:19). The believer can be content no matter what the outward circumstances. (Php 4:11-13) Believers are content to know the Father (Jn 14:8-9) and depend on his grace (2 Co 12:9-10; compare 2 Co 9:8-11).’ (Holman)

‘Epicurus said of himself: “To whom little is not enough nothing is enough. Give me a barley cake and a glass of water and I am ready to rival Zeus for happiness.” And when someone asked him for the secret of happiness, his answer was: “Add not to a man’s possessions but take away from his desires.”‘ (DSB)

‘The rock of our present day is that no one knows how to live upon little. The great men of antiquity were generally poor…. It always seems to me that the retrenchment of useless expenditure, the laying aside of what one may call the relatively necessary, is the high road to Christian disentanglement of heart, just as it was to that of ancient vigour. The mind that has learned to appreciate the moral beauty of life, both as regards God and men, can scarcely be greatly moved by any outward reverse of fortune; and what our age wants most is the sight of a man, who might possess everything, being yet willingly contented with little. For my own part, humanly speaking, I wish for nothing. A great soul in a small house is the idea which has touched me more than any other.’ (Lacordaire)

‘The word “poverty” has come to sound so negative and extreme in our ears that I prefer the word “simplicity,” because it puts the emphasis on the right points..Our enemy is not possessions but excess. Our battle-cry is not “nothing” but “enough”.’ (John V. Taylor)

Money cannot buy happiness. ‘Despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, most people still believe that money brings happiness. Rich people craving greater riches can be caught in an endless cycle that only ends in ruin and destruction. How can you keep away from the love of money? Paul gives us some guidelines: (1) realize that one day riches will all be gone (1 Tim 6:7, 17); (2) be content with what you have (1 Tim 6:8); (3) monitor what you are willing to do to get more money (1 Tim 6:9-10); (4) love people more than money (1 Tim 6:11); (5) love God’s work more than money (1 Tim 6:11); (6) freely share what you have with others (1 Tim 6:18).’ (See Prov 30:7-9 for more on avoiding the love of money.) (HBA)

See Ps 37:16.

Paul will now contrast two attitudes of the poor, the attitude of contentment, v7f, and the attitude of covetousness, v9f.

On this fundamental truth, see Job 1:21 Ec 5:15. Our life on earth is a brief pilgrimage between two moments of absolute poverty.

We can take nothing out of it – ‘Whatever a man amasses by the way is in the nature of luggage, no part of his truest personality, but something he leaves behind at the toll-bar of death.’ (Simpson)

‘As the officiating minister said at the funeral of a wealthy lady, when asked by the curious how much she had left, “She left everything.”‘ (Stott)

‘A shroud, a coffin, and a grave, are all that the richest man in the world can have from his thousands’ (MHC)

‘Materialism is an obsession with material things. Asceticism is the denial of the good gifts of the Creator. Pharisaism is binding ourselves and other people with rules. Instead, we should stick to principles. The principle of simplicity is clear. Simplicity is the first cousin of contentment. Its motto is, “We brought nothing into this world, and we can certainly carry nothing out.” It recognises that we are pilgrims. It concentrates on what we need, and measures this by what we use. It rejoices in the good things of creation, but hates waste and greed and clutter. It knows how easily the seed of the Word is smothered by the “cares and riches of this life.” It wants to be free of distractions, in order to love and serve God and others.’ (Stott, Authentic Christianity, 363)

Given the truth of v7, what then should be our attitude towards material things? It should be contentment with the necessities of life.

Clothing – the word (skepasma, occurring only here) can mean covering, shelter, clothing, house.

The reference to food and clothing echoes the words of Jesus in Mt 6:25-34 in a passage on worry, the antithesis of contentment.

Is it wrong to possess more than the basic necessities of life? Probably not, because ‘what Paul is defining is not the maximum that is permitted to the believer, but the minimum that is compatible with contentment.’ (Stott) he is not advocating austerity or asceticism, but contentment instead of materialism and covetousness. Stott notes that ‘this does not mean that we are free to go to the opposite extreme of extravagance. He quotes the Evangelical Commitment to Simple Lifestyle (1980):- ‘We resolve to renounce waste and oppose extravagance in personal living, clothing and housing, travel and church buildings. We also accept the distinction between necessities and luxuries, creative hobbies and empty status symbols, modesty and vanity, occasional celebrations and normal routine, and between the service of God and slavery to fashion. Where to draw the line requires conscientious thought and decision by us, together with members of our family.’

Paul is not yet talking about the rich: their turn will come in v17. He is talking about the poor who want to become rich, who are motivated by the ‘love of money’, v10.

‘Those who have fixed their desires upon wealth as their highest good soon find they are following a downward path, which brings them sorrow in this world and eternal perdition in the next.’ (Wilson)

As Stott says, the OT has much to say about covetousness. Money is addictive, Ec 5:10. We are not to be overawed by the wealthy, for they will leave their wealth behind, Ps 49:10, 166ff. Covetousness itself will lead to its own punishment, Pr 28:20. We are to pray neither for poverty nor riches, but only the necessities of life, Prov 30:7ff. Jesus himself endorsed this teaching, Lk 12:15ff. Scripture presents a number of cautionary tales in this respect, as in the stories of Adam and Eve, Achan, Judas, and Ananias and Sapphira, Gen 3:6 Jos 7:20-21 Mt 26:14ff Jn 12:4ff Acts 5:1ff.

People who want to get rich fall into temptation and a trap, thus doing to themselves what they prayed God would not do to them. Their many foolish and harmful desires lead them readily into corrupt and dishonest practices and even theft. Because their covetousness can never be satisfied, their downward spiral leads them into ruin and destruction – in this life, debt, disillusionment, friendlessness; in the life to come, condemnation. ‘The irony is that those who set their hearts on gain end in total loss, the loss of their integrity and indeed of themselves.’ (Stott) Cf. Mk 8:36.

‘Paul was always careful not to use his calling and ministry as a means of making money. In fact, he even refused support from the Corinthian church so that no one could accuse him of greed. (1 Co 9:15-19) He never used his preaching as “a cloak of covetousness.” (1 Th 2:5) What a tragedy it is today to see the religious racketeers who prey on gullible people, promising them help while taking away their money.’ (Wiersbe)

‘Some are not content with ‘daily bread,’ but desire to have their barns filled, and heap up silver as dust; which proves a snare to them. ‘They that will be rich fall into a snare.’ 1 Ti 6:9. Pride, idleness, wantonness, are three worms that usually breed of plenty. Prosperity often deafens the ear against God. ‘I spake unto thee in thy prosperity, but thou saidst, I will not hear.’ Jer 22:21. Soft pleasures harden the heart. In the body, the more fat, the less blood in the veins, and the less spirits; so the more outward plenty, often the less piety. Prosperity has its honey, and also its sting; like the full of the moon, it makes many lunatic. The pastures of prosperity are rank and surfeiting. Anxious care is the mains genius, the evil spirit that haunts the rich man, and will not let him be quiet. When his chests are full of money, his heart is full of care, either how to manage or how to increase, or how to secure what he has gotten. Sunshine is pleasant, but sometimes it scorches. Should it not make us content with what allowance God gives, if we have daily bread, though not dainties? Think of the danger of prosperity! The spreading of a full table may be the spreading of a snare. Many have been sunk to hell with golden weights. The ferry-man takes in all passengers, that he may increase his fare, and sometimes to the sinking of his boat. ‘They that will be rich fall into many hurtful lusts, which drown men in perdition.’ 1 Ti 6:9. The world’s golden sands are quicksands, which should make us take our daily bread, though it be but coarse, contentedly. What if we have less food, we have less snare; if less dignity, less danger. As we lack the rich provisions of the world, so we lack the temptations.’ (Thomas Watson)

‘We may be very sure that riches and worldly greatness are no certain marks of God’s favor. They are often, on the contrary, a snare and hindrance to a man’s soul. They make him love the world and forget God. What does Solomon say? “Do not wear yourself out to get rich; have the wisdom to show restraint.” (Pr 23:4) What does Paul say? “People who want to get rich fall into temptation and a trap and into many foolish and harmful desires that plunge men into ruin and destruction.”‘ (J.C. Ryle)

‘Covetousness, or the desire to be rich, is an evil against which the Scriptures frequently warn. The love of money is described as the root of all kinds of evil. (1 Tim 6:9-10) Consequently a spirit of contentment with such things as God has given is a virtue inculcated in both Testaments.’ (Ps 62:10; 1 Tim 6:8; Heb 13:5) (NBD)

The love of money is the root of all evils – This saying appears to have been a current proverb, found in various forms in both Greek and Jewish literature. Cf.Heb 13:5.

The saying is often misquoted, as though it said, ‘Money is the root of all evil.’ But it actually says that ‘the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil.’

All kinds of evil – ‘What…are the evils of which money is a major root or cause? A long list could be given. Avarice leads to selfishness, cheating, fraud, perjury and robbery, to envy, quarrelling and hatred, to violence and even murder. Greed lies behind marriages of convenience, perversions of justice, drug-pushing, pornography sales, blackmail, the exploitation of the weak, the neglect of good causes, and the betrayal of friends.’ (Stott) ‘The sentiment is, that there is no kind of evil to which the love of money may not lead men, when it once fairly takes hold of them.’ (Fairbairn) Paul, however focuses on two effects of covetousness: it has led some people to wander from the faith, and it has led these people into misery. See Mt 26:15

Paul does not expand on what these many griefs might be. ‘But they could include worry and remorse, the pangs of a disregarded conscience, the discovery that materialism can never satisfy the human spirit, and final despair. Jay Gould, the nineteenth-century American financier, exclaimed with his dying words, “I’m the most miserable devil in the world.”‘ (Stott) Their love of money brought them pangs of conscience, the anguish of disillusionment, and barrenness.

‘When Paul describes the love of money as a root of all kinds of evil (10), it is important to draw a distinction between money itself and the love of it. As a commodity there is nothing wrong with it, but when it becomes the object of overriding desire it leads to evil. There is no suggestion that love of money is the sole or even main cause of evil. Paul’s concern here is to point out the spiritual risks involved in money-grabbing. This is what he means by wandering from the faith. Paul does want us to see, however, that wherever any kind of evil occurs, money easily gets mixed up with it. Illicit sex becomes the business of prostitution; the problem of drug abuse is as strongly empowered by money as it is by addiction; the love of power is inevitably tied to the deployment of wealth, and so on. It is significant that Paul speaks of those concerned as having pierced themselves with griefs. The results are seen as self-inflicted – the inevitable result of loving the wrong thing.’ (NBC)

‘This is a truth of which the great classical thinkers were as conscious as the Christian teachers. “Love of money,” said Democritus, “is the metropolis of all evils.” Seneca speaks of “the desire for that which does not belong to us, from which every evil of the mind springs.” “The love of money,” said Phocylides, “is the mother of all evils.” Philo spoke of “love of money which is the starting-place of the greatest transgressions of the Law.” Athenaeus quotes a saying: “The belly’s pleasure is the beginning and root of all evil.”‘ (DSB)

‘As sick men do use to love health better than those that never felt the want of it; so it is too common with poor men to love riches better than the rich that never needed. And yet, poor souls, they deceive themselves, and cry out against the rich, as if they were the only lovers of the world, when they love it more themselves though they cannot get it.’ (Richard Baxter)

‘When a man is to travel into a far country…one staff in his hand may comfortably support him, but a bundle of staves would be troublesome. Thus a competency of these outward things may happily help us in the way ot heaven, whereas abundance may be hurtful.’ (Richard Sibbes)

‘Wealth is like a viper, which is harmless if you know how to take hold of it; but, if you do not, it will twine round your hand and bite you.’ (Irenaeus)

‘We must impart our wealth benevolently; avoiding the extremes of meanness and ostentation. We must not let our love of the beautiful run into selfishness or excess; lest it should be said of us, “His horse, or his farm, or his servant, or his plate, is worth fifteen talents, while he himself would be dear at three farthings.’ (Clement of Alexandria)

Stott points out that ‘this whole passage (vv6-10), which is the apostle’s charge to the Christian poor, both the contented poor and the covetous poor, is calculated to make Christianity’s critics explode with anger. “This is precisely what Marx meant,” they will say, “when he called religion ‘the opium of the people’. Christianity instills into the proletariat a false contentment with their lot. It encourages the poor to accept their poverty, and to acquiesce in the status quo (instead of rebelling against it), on the flimsy ground that they will be compensated in the next world.”‘ We will have to concede, says Stott, that Marx was partly right in his analysis: the contentment that Christianity teaches has been used by some to defend the exploitation of the poor and to keep them in their oppression, while promising them freedom in heaven. But Paul does not do this: (a) he is not speaking in this passage of destitution, but of a simplicity of lifestyle; (b) the contentment he is speaking of acquiescence in social injustice. Personal contentment is quite compatible with the quest for justice, especially if it is justice for other people that we are fighting for.

‘Money will buy a bed but not sleep, books but not brains, food but not appetite, fine clothes but not beauty, medicine but not health, luxury but not culture, amusement but not happiness, a crucifix but not a saviour, a temple but not heaven.’ (Naismith, 1200 Notes, Quotes and Anecdotes)

Some people, eager for money, have wandered from the faith – Was this, perhaps, what had happened to Demas, 2 Tim 4:10?

(i) The desire for money tends to be a thirst which is insatiable. There was a Roman proverbial saying that wealth is like sea-water; so far from quenching a man’s thirst, it intensifies it. The more he gets, the more he wants.

(ii) The desire for wealth is founded on an illusion. It is founded on the desire for security; but wealth cannot buy security. It cannot buy health, nor real love; and it cannot preserve from sorrow and from death. The security which is founded on material things is foredoomed to failure.

(iii) The desire for money tends to make a man selfish. If he is driven by the desire for wealth, it is nothing to him that someone has to lose in order that he may gain. The desire for wealth fixes a man’s thoughts upon himself, and others become merely means or obstacles in the path to his own enrichment. True, that need not happen; but in fact it often does.

(iv) Although the desire for wealth is based on the desire for security, it ends in nothing but anxiety. The more a man has to keep, the more he has to lose and, the tendency is for him to be haunted by the risk of loss. There is an old fable about a peasant who rendered a great service to a king who rewarded him with a gift of much money. For a time the man was thrilled, but the day came when he begged the king to take back his gift, for into his life had entered the hitherto unknown worry that he might lose what he had. John Bunyan was right:

“He that is down needs fear no fall, He that is low, no pride; he that is humble ever shall Have God to be his guide. I am content with what I have, Little be it or much; And, Lord, contentment still I crave, Because thou savest such. Fullness to such a burden is That go on pilgrimage; Here little, and hereafter bliss, Is best from age to age.”

(v) The love of money may easily lead a man into wrong ways of getting it, and therefore, in the end, into pain and remorse. That is true even physically. He may so drive his body in his passion to get, that he ruins his health. He may discover too late what damage his desire has done to others and be saddled with remorse.

To seek to be independent and prudently to provide for the future is a Christian duty; but to make the love of money the driving-force of life cannot ever be anything other than the most perilous of sins. (DSB)

6:11 But you, as a person dedicated to God, keep away from all that. Instead pursue righteousness, godliness, faithfulness, love, endurance, and gentleness. 6:12 Compete well for the faith and lay hold of that eternal life you were called for and made your good confession for in the presence of many witnesses.

11-16 Priorities for the man of God

Paul’s appeal to the man of God is ethical, doctrinal, and experiential, vv11f. He is to flee from evil and pursue goodness; he is to turn from error and fight for the truth; he is to live to the full the eternal life he has already received. All three aspects are vital. Doctrine, ethics, and spirituality belong together, and cannot survive without one another.

‘In 1 Ti 6:11-14, Paul lists four characteristics of such a man of God: he is marked by what he flees from, follows after, fights for, and is faithful to.’ (McArthur, Rediscovering Expository Preaching)

But you – A contrast will now be drawn between the false teachers and their worldly ambition and what Timothy should be. They were men of the world; he is to be a man of God.

Man of God – ‘That is one of the great Old Testament titles. It is a title given to Moses. Deut 33:1 speaks of “Moses, the man of God.” The title of Ps 90 is, “A Prayer of Moses the man of God.” It is a title of the prophets and the messengers of God. God’s messenger to Eli is a man of God. (1 Sa 2:27) Samuel is described as a man of God. (1 Sa 9:6) Shemaiah, God’s messenger to Rehoboam, is a man of God.’ (1 Ki 12:22) (DSB) Fee agrees that the background for this title is found in the OT, where in each case it refers to a minister or agent of God. He adds that it serves here to underline the contrast with the false teachers, who can no longer be thought of as God’s ministers.

This designation applies primarily to Timothy, as a man called to public ministry. By extension it may, of course, be applied to others with similar ministries. Any further extrapolation (‘we are all men and women of God’) rather misses the point.

Although it is well to be reminded of our sinful natures, it is also good to have our attention drawn to the essential nobility of the Christian calling. It is one thing to have our humiliating past thrown in our face, it is another to have set before us our potential future. The expression occurs again in 2 Ti 3:17.

Timothy will not be appealed to by name until v20. He is here call a ‘man of God’ in contrast to the false teachers (vv4-10) who are men of the world in their conceit, quarrelsomeness, and covetousness. The contrast is evident from the words but you…flee from all this.

Here, in this verse, is what the man of God must flee from, and what he should pursue. People are running in all directions. The man of God should run in the right direction. He is to flee from all of this – the love of money, and the many evils associated with it. ‘Not all unity is good, and not all division is bad. There are times when a servant of God should take a stand against false doctrine and godless practices, and separate himself from them. He must be sure, however, that he acts on the basis of biblical conviction and not because of a personal prejudice or a carnal party spirit.’ (Wiersbe)

‘”Flee” is from the Greek word pheugo, from which the English word fugitive is derived. It is used in extrabiblical Greek literature to speak of running from a wild animal, a poisonous snake, a deadly plague, or an attacking enemy. It is an imperative in the present tense and could be translated “keep on continually fleeing.” A man of God is a lifelong fugitive, fleeing those things that would destroy him and his ministry. In other places Paul lists some of the threats: immorality, (1 Co 6:18) idolatry, (1 Co 10:14) false teaching (1 Ti 6:20 and 2 Ti 2:16), and false teachers, (2 Ti 3:5) as well as youthful lusts.’ (2 Ti 2:22) (McArthur, Rediscovering expository preaching)

‘We human beings are great runners. It is natural for us to run away from anything which threatens us. To run from a real danger is common sense, but to run from issues we dare not face or from responsibilities we dare not shoulder is escapism. Instead, we should concentrate on running away from evil. We also run after many things which attract us – pleasure, promotion, fame, wealth and power. Instead, we should concentrate on the pursuit of holiness. There is no particular secret to learn, no formula to recite, no technique to master. The apostle gives us no teaching on “holiness and how to attain it.” We are simply to run from evil as we run from danger, and to run after goodness as we run after success. That is, we have to give our mind, time and energy to both flight and pursuit. Once we see evil as the evil it is, we will want to flee from it, and one we see goodness as the good it is, we will want to pursue it.’ (Stott)

‘Separation without positive growth becomes isolation. We must cultivate these graces of the Spirit in our lives, or else we will be known only for what we oppose rather than for what we propose.’ (Wiersbe)

The ethical qualities listed here seem to be presented in three pairs.

Righteousness – A comprehensive virtue, which consists in doing one’s duty both to God and man. Perhaps it refers particularly to justice and fairness in dealing with others. Godliness is ‘The reverence of the man who never ceases to be aware that all life is lived in the presence of God.’ (DSB) we are called to worship God, not money.

Faith – here means ‘fidelity’, ‘trustworthiness’; loyalty to God no matter what.

Endurance is the unswerving constancy to faith and piety in spite of adversity and suffering. It is patience in difficult circumstances, whereas gentleness is patience with difficult people. Both are signs of strength, not weakness; of power under control. ‘The Greek word is paupatheia. It is translated gentleness but is really untranslatable. It describes the spirit which never blazes into anger for its own wrongs but can be devastatingly angry for the wrongs of others. It describes the spirit which knows how to forgive and yet knows how to wage the battle of righteousness. It describes the spirit which walks at once in humility and yet in pride of its high calling from God. It describes the virtue by which at all times a man is enabled rightly to treat his fellow-men and rightly to regard himself.’ (DSB)

Fight the good fight of the faith – See 2 Tim 4:7. ‘Timothy’s duty will involve fight as well as flight.’ (Stott) Here is the doctrinal part of Paul’s charge to the man of God.

The definite article (‘the faith’) is to be noted. There is concern running through the Pastorals for ‘the faith’, that is, the apostolic faith, precisely because some have wandered away from it, v10, 21. Cf. 1 Tim 2:4; 3:15; 4:3,6; 6:1,20; 2 Tim 1:12,14; Tit 1:9; 2:1.

Just as, ethically, we are to flee evil and pursue goodness, v11, so doctrinally, we are to avoid error, v20, and contend for the truth, vv12, 20.

‘Fighting is an unpleasant business – undignified, bloody, painful and dangerous. So is controversy, that is, fighting for truth and goodness. It should be distasteful to all sensitive spirits. There is something sick about those who relish it. Nevertheless, it is a “good fight;” it has to be fought. For truth is precious, even sacred. Being truth from God, we cannot neglect it without affronting him. It is also essential for the health and growth of the church. So whenever truth is imperilled by false teachers, to defend it is a painful necessity. Even the ‘gentleness’ we are to pursue (the last word of v11) is not incompatible with fighting the good fight of the faith.’ (Stott)

‘Observe, It is a good fight, it is a good cause, and it will have a good issue.’ (MHC)

Now comes the experiential part of Paul’s charge to the man of God.

Eternal life – The emphasis is on quality, rather than duration. It is possessed now, 1Ti 1:16; 2 Tim 1:10, and also hoped for in the future, Tit 1:2; 3:17. It may be that the future aspect is at the forefront of Paul’s mind here, if Paul is completing his metaphors of the race and the fight and alluding to the prize at the end of each.

‘This expression occurs in the Old Testament only in Dan 12:2 (R.V., everlasting life). It occurs frequently in the New Testament (Mt 7:14; 18:8,9; Lk 10:28; compare Lk 18:18). It comprises the whole future of the redeemed, (Lk 16:9) and is opposed to eternal punishment. (Mt 19:29; 25:46) It is the final reward and glory into which the children of God enter; (1 Ti 6:12,19 Rom 6:22; Gal 6:8; 1 Tim 1:16; Rom 5:21) their Sabbath of rest (Heb 4:9; compare Heb 12:22).

The newness of life which the believer derives from Christ (Rom 6:4) is the very essence of salvation, and hence the life of glory or the eternal life must also be theirs. (Rom 6:8 2 Ti 2:11,12 Rom 5:17,21 8:30 Eph 2:5,6) It is the gift of God in Jesus Christ our Lord. (Rom 6:23) The life the faithful have here on earth (Jn 3:36 5:24 6:47,53-58) is inseparably connected with the eternal life beyond, the endless life of the future, the happy future of the saints in heaven.’ (Mt 19:16,29 25:46) (Easton’s Bible Dictionary)

But why is Timothy urged to take hold of eternal life? Why be asked to take hold of something one already possesses? The idea is of making it completely his own, of enjoying it and living it to the full.

To which you were called when you made your good confession in the presence of many witnesses – Perhaps Timothy is being reminded of his baptismal vows, although some think the reference is to his ‘ordination’, cf. 4:14 2 Ti 2:2.

As he is challenged to face the future, Timothy is to remember the past:-

1. Remember the public confession you made when you received salvation, v12. ‘The earliest of all Christian confessions was the simple”] creed: “Jesus Christ is Lord.” (Rom 10:9 Php 2:11) But it has been suggested that behind these words to Timothy lies a confession of faith which said: “I believe in God the Almighty, Creator of heaven and earth, and in Christ Jesus who suffered under Pontius Pilate and will return to judge; I believe in the Resurrection from the dead and in the life immortal.” It may well have been a creed like that to which Timothy gave his allegiance. So, then, first of all, he is reminded that he is a man who has given his pledge. The Christian is first and foremost a man who has pledged himself to Jesus Christ.’ (DSB)

2. Remember that you stand with Christ when you confess your faith, v13.

3. Remember that Christ is coming again, v14. ‘The Christian is not working to satisfy men; he is working to satisfy Christ. The question he must always ask himself is not: “Is this good enough to pass the judgment of men?” but: “Is it good enough to win the approval of Christ?”‘ (DSB)

4. Remember that your whole life is lived before God almighty, v15.

See also 1 Tim 1:3-11; 2:5-7; 3:14-15.

6:13 I charge you before God who gives life to all things and Christ Jesus who made his good confession before Pontius Pilate, 6:14 to obey this command without fault or failure until the appearing of our Lord Jesus Christ 6:15—whose appearing the blessed and only Sovereign, the King of kings and Lord of lords, will reveal at the right time. 6:16 He alone possesses immortality and lives in unapproachable light, whom no human has ever seen or is able to see. To him be honor and eternal power! Amen.

Now follow, vv13-16, strong grounds for the appeal Paul has just made. The first is the awareness of the conscious presence of God.

Some have found in these verses signs of a baptismal confession.

In the sight of God…and of Christ – Paul was aware that the whole of life is lived under the divine gaze. See Psa 139.

Christ Jesus, who while testifying before Pontius Pilate made the good confession – Timothy is to follow in the footsteps of the Master himself, who was faithful to the truth about himself even in his moment of ultimate testing. Just as Timothy had confessed Jesus as Lord at his baptism, so Jesus himself had testified to his own kingship before Pilate, Mk 15:2.

Robert M. Price comments, in passing, that 1 Timothy must be ‘very late’, since it ‘presupposes the Gospel of John (the only Gospel in which Jesus “made a good confession before Pontius Pilate”)’ (The Historical Jesus: Five Views). This opinion unaccountably leaves Mark (almost universally considered to be the earliest of the canonical Gospels, and much earlier that John) out of the equation, and also fails to consider that records of what Jesus said and did would have been circulating long before they were written up by the four evangelists.

This command may refer to the appeal Paul has just made to the man of God in vv11f, or to the whole teaching of this letter, or even to the entire law of Christ.

‘He is to remember that his life and work must be made fit for him to see. The Christian is not working to satisfy men; he is working to satisfy Christ. The question he must always ask himself is not: “Is this good enough to pass the judgment of men?” but: “Is it good enough to win the approval of Christ?”‘ (DSB)

Until the appearing of our Lord Jesus Christ – Here is the second ground for the appeal to the man of God.

‘It is often suggested that this last phrase implies that Paul (or a later author) is writing at a time when the imminence of the Parousia is no longer alive. But that is to read far too much into one phrase (read, of course, in light of 2 Tim. 2:6–8). It also misses the eschatological urgency of these letters (1 Tim. 4:1; 2 Tim. 3:1), as well as the ambiguity elsewhere in Paul. As early as 1 Corinthians, the very letter that has so much of the urgency in it (7:29–31), Paul speaks of “awaiting the revelation” (1:7; cf. 11:26) and in Philippians one finds the same tension between his readiness to die (1:21–23) and “awaiting the Lord Jesus from heaven” (3:20–21). If the present text implies anything, it is that Timothy will experience the Parousia, and that scarcely reflects the perspective of a church settling in for a long life in the world.’ (Fee)

Which God will bring about in his own time – Paul is still convinced about the return of Christ, and still uncertain about its time, cf. Mk 13:32; Acts 1:7; 1 Jn 5:1.

‘This assurance about the divine timetable is a notable feature of the Pastorals. Whether Paul is alluding to the first coming of Christ (past), the proclamation of the gospel (present) or his appearing (future), each event occurs in God’s “own” or “appointed” time.’ (1 Ti 2:6; 6:16; Tit 1:3) (Stott)

God, the blessed and only Ruler – Both mentions of ‘God’ in this verse are translators’ glosses. In fact, most translations either supply or imply ‘God’:-

(a) some think that the referent is ‘our Lord Jesus Christ’. It is true that ‘King of kings and Lord of lords is used of Christ in Rev 17:14; 19:16. But it can scarcely be said of our incarnate Saviour that ‘no one has seen’ him (v16).

(b) others think that the referent is ‘God’ (the Father). This is reflected, of course, in the NIV translation and others. It is also supported by Calvin, Fee, Guthrie, NBC, Hendriksen, Mounce, and many other commentators. Fee (Pauline Christology) remarks that what Paul has said about Jesus focuses very much upon his incarnation; the passage ends, however, with a robust re-assertion of monotheism: ‘However we are to understand Paul’s understanding of the ontological relationship between God and Christ, Father and Son, he will not let the reality of Christ’s genuine deity overrule his basic, absolute monotheism.’

v15f. This is one of a number of doxologies (Lk 2:14; 1 Ti 1:17; Rev 4:8, for example) which may have been used in public worship. The motivation to respond to the appeal to the man of God, and the willingness to leave the timing of all this in his hands, comes from a knowledge of the kind of God we worship and serve.

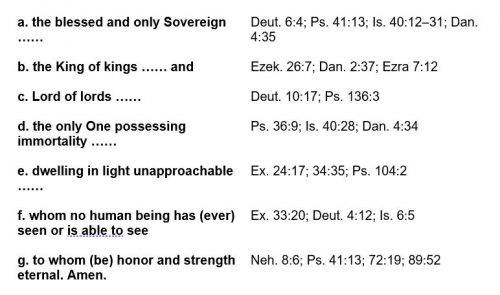

Hendriksen identifies many OT parallels:

‘Much of [this doxology] seems to be composed in opposition to emperor worship, which explains Paul’s motivation in using it: (1) the epiphany of Jesus is the true manifestation of divinity, not the appearance of the emperor; (2) God alone has immortality, not the dead emperor; (3) it is God and God alone who is the King over all who rule and Lord over all who would be lords; and (4) God is the only sovereign to whom alone belongs honor and might forever. This is another witness to the necessity of reading the PE in light of their historical background, the heresy in Ephesus, and the teachings that pervaded the city.’ (Mounce, WBC)

Here are four aspects of God’s sovereign power. He is (a) invincible, the King of kings and Lord of lords. Cf. Deut 10:17; Ps 136:2-3; Rev 17:14; 19:16. No human ruler can challenge the authority of God. He is (b) immortal, v16; not subject to decay or death. Ours is only a derivative immortality; God is immortal in essence. God is (c) inaccessible, for lives in unapproachable light, v16. No darkness of any kind can enter his presence. He is (d) invisible, whom no one has seen or can see. We can only know God so far as he has been pleased to make himself known.

He alone possess immortality – ‘athanasia‘, the negation of death.

Guthrie notes that

‘already in 1 Tim 1:17 the quality immortal is applied to God, although there the adjective aphthartos is used, while here the noun athanasia (immortality) occurs. Both words are found in parallel clauses in 1 Corinthians 15:53–54 with apparently no difference of meaning.’

Peterson comments:

‘Two Greek words, athanasia and aphtharsia, are often translated “immortality.” When athanasia refers to God in 1 Timothy 6:16, Paul seems to be referring to God’s independent life or inherent self-existence. When athanasia refers to the resurrection of believers in 1 Corinthians 15:53-54, Paul is stressing that through Christ’s resurrection, believers will be immune from death forever. Aphtharsia (see Rom. 2:7; 1 Cor. 15:42, 52-54; 2 Tim. 1:10) generally connotes immunity from decay and is typically linked with eternal life.’ (Hell Under Fire)

‘He alone possesses “immortality.” This must not be confused with “endless existence.” To be sure, that, too, is implied, but the concept “immortality” is far more exalted. It means that God is life’s never-failing Fountain…This immortality is the opposite of “death,” as is clear from the derivation of the word both in English and in Greek. “Athanasia” is deathlessness. It is fulness of life, “imperishable” blessedness, the inalienable enjoyment of all the divine attributes.’ (Hendriksen)

Proponents of conditional immortality make much of this text, arguing that since God alone has immortality in and of himself, the immortality of human creatures need not (and indeed does not) extend to all, but only to those who receive the gift of ‘eternal life’. Others, it is asserted, suffer eternal death (i.e. annihilation). We would comment that the present verse is not decisive in the debate as to whether all, or only some, human beings are immortal (in this derived sense); the argument, ‘if it proves anything, proves too much. In fact, God who alone has immortality in himself may and does communicate it to some of his creatures.’ (Nicole, EDT, 2nd ed., art. ‘Annihilationism’)

Those who teach the immortality of the human soul might argue:-

(a) that although God alone is immortal in himself, he communicates immortality to others. This was the view of Calvin. Matthew Henry comments: ‘He only has immortality; he only is immortal in himself, and has immortality as he is the Fountain of it, for the immortality of angels and spirits is derived from him’. For some, the immortality of the human soul derives from our being made in God’s image: according to the Westminster Confession: ‘‘After God had made all other creatures, he created man, male and female, with reasonable and immortal souls’.

(b) that although the human body is mortal, the soul is immortal. Swete comments: ‘God is immortal in the sense that he cannot die . . . God “only hath immortality” such as this. Man is immortal in the sense that there is in him that which does not die. His body dies, but his soul survives. It lives on after it has left the body. His identity is not lost when he dies; his true self, the ultimate being and personality of the man, remains as it was before death . . . Not all of him dies; there is a part of him, and by far the more essential [which cannot die].’ (Cited by Fudge, The Fire That Consumes, 3rd ed.)

Hughes argues: ‘Man’s formation in the image of God does indeed imply his possession of life in a manner that transcends that of other animate creatures; but it cannot mean the possession of life in the same sense as that in which God possesses it, if only because God possesses life absolutely, from eternity to eternity, whereas man possesses it derivatively and subject to the good pleasure of his Creator. The immortality of man or of the human soul is not then a necessary conclusion from this premise.’ (Christopher M. Date, Gregory G. Stump, Joshua W. Anderson. Rethinking Hell: Readings in Evangelical Conditionalism (pp. 187-188). Cascade Books, an Imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers. Kindle Edition.)

A belief in the immortality of the soul has clear implications for the doctrine of everlasting punishment. Fudge: ‘If every soul lives forever, there are only two possibilities concerning those who go to hell. Either they will endure unending conscious torment, or else they will be restored to God’s favor and be delivered from hell.’ (Fudge, Edward William. The Fire That Consumes: A Biblical and Historical Study of the Doctrine of Final Punishment, Third Edition (p. 25). Cascade Books, an imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers. Kindle Edition.)

Calvin, as noted above, taught that, although God alone is immortal, he confers immortality on human beings. Philip Hughes summarises and critiques Calvin’s position:-

‘In his comments on 1 Tim 6: 16 Calvin made it plain that he did not regard immortality as inseparable from human nature or from the essence of the soul. “I reply, when it is said, that God alone possesses immortality,” he wrote, “it is not here denied that he bestows it, as he pleases, on any of his creatures.” To say God alone is immortal is to imply that he “has immortality in his power; so that it does not belong to creatures, except so far as he imparts to them power and vigour.” This means, further, that “if you take away the power of God which is communicated to the soul of man, it will instantly fade away.” Thus Calvin concluded that “Strictly speaking, therefore, immortality does not subsist in the nature of souls . . . but comes from another source, namely, the secret inspiration of God.” The question that remains unanswered in the position represented by Calvin is this: if it is granted that immortality is a gift imparted by God and, further, that the being to whom it is imparted would “instantly fade away” were God’s power to be removed, what grounds are there for concluding that immortality is a permanent gift that will not under any circumstances be removed, and accordingly that no rational being will ever relapse into nonexistence, or, in other words, suffer destruction? It is a conclusion that (as we shall see) seems to rest largely on the supposition that the endless bliss of the redeemed requires to be balanced by the endless punishment of the damned.’

in Christopher M. Date, Gregory G. Stump, Joshua W. Anderson. Rethinking Hell: Readings in Evangelical Conditionalism (pp. 189-190). Cascade Books, an Imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers. Kindle Edition.

Whom no one has seen or can see – ‘Even a beatific vision of heaven will not consist of a sight of God as God, but rather as he shines forth in a manifestative and communicative way in the person of Christ, as suited to finite capacities.’ (A.W. Pink)

‘It is impossible for a sinful human to approach the holy God. It is only through Jesus Christ that we can be accepted into his presence. Jacob saw God in one of his Old Testament appearances on earth; (Gen 32:30) and God allowed Moses to see some of his glory. (Ex 33:18-23) “No man hath seen God at any time” (Jn 1:18) refers to seeing God in his essence, his spiritual nature. We can only see manifestations of this essence, as in the person of Jesus Christ.’ (Wiersbe)

Who lives in unapproachable light – God may be said to have a throne (a) of glory, 1 Ti 6:16; (b) of government, Ps 9:4,7; (c) of justice, Ps 143:2; (d) of final judgement, 2 Co 5:10; and, (e) of grace, 2 Co 5:19; Rom 3:25; Heb 4:16; 1 Jo 2:2 4:10.

Comparing God’s throne of glory with his throne of grace, Robert Traill says of the former, ‘this no man can approach to. Of this the apostle speaks, 1 Ti 6:16. He dwelleth in light that no man can approach to, whom no man hath seen, nor can see. Marvellous is this light. We find the more light there be in or about a person or thing, the more easily and clearly it is perceived: as the sun is such a glorious body, that though it be at a vast distance from the earth we dwell on, we yet can take it up with our eyes immediately. As soon as it shines, we can see it, because of its light. It is its own light, and nothing else, that doth, or can discover it. If the sun did withdraw its own light, all the eyes of men, and all the artificial fire and light men can make, would never help us to find it out. But such is the majesty of God, that he is clothed with it. (Ps 93:1) Men are dazzled and confounded by a little ray of his glory: With God is terrible majesty. (Job 37:22) This is not the throne we are called to come unto. They are but triflers in religion, that know not in their experience how overwhelming the views and thoughts of God’s majesty and glory are, when he is not seen as on a throne of grace. I remembered God, and was troubled, saith one saint. (Ps 77:3) I am troubled at his presence; when I consider, I am afraid of him, saith another. (Job 23:15) No wonder Manoah said unto his wife, we shall surely die, because we have seen God (Jude 13:22) when a view of the heavenly glory of Jesus Christ makes John, who was wont to lean on his bosom in his humbled state, to fall down at his feet as dead.’ (Rev 1:17)

To him be honour and might forever – It is natural for Paul to break in doxology as he reflects on the sovereignty of God. Contemplation on the true nature of the godhead must prompt either trebling fear or fervent praise.

6:17 Command those who are rich in this world’s goods not to be haughty or to set their hope on riches, which are uncertain, but on God who richly provides us with all things for our enjoyment. 6:18 Tell them to do good, to be rich in good deeds, to be generous givers, sharing with others. 6:19 In this way they will save up a treasure for themselves as a firm foundation for the future and so lay hold of what is truly life.

Those who are rich in this present world – Paul has previously addressed the Christian poor; now he speaks to the Christian rich. He is therefore returning, after a digression, to the subject of money.

‘Sometimes we think of the early Church as composed entirely of poor people and slaves. Here we see that even as early as this it had its wealthy members. They are not condemned for being wealthy nor told to give all their wealth away; but they are told what not to do and what to do with it.

Their riches must not make them proud. They must not think themselves better than other people because they have more money than they. Nothing in this world gives any man the right to look down on another, least of all the possession of wealth. They must not set their hopes on wealth. In the chances and the changes of life a man may be wealthy today and a pauper tomorrow; and it is folly to set one’s hopes on what can so easily be lost.

They are told that they must use their wealth to do good; that they must ever be ready to share; and that they must remember that the Christian is a member of a fellowship. And they are told that such wise use of wealth will build for them a good foundation in the world to come. As someone put it: “What I kept, I lost; what I gave I have.” (DSB)

Note that Paul does not demand that the rich give up their money. Instead, he warns them of the dangers of riches, and then sets out their responsibilities.

The wealthy are tempted to be arrogant. Money tends to make people feel self-important, contemptuous of other. They may boast of their many possessions. See Deut 8:14; Eze 28:5.

But the rich are also to be commanded not to put their hope in wealth. Wealth and material possessions are uncertain, Mt 6:19. They are subject to the ravages of moths, rust, and thieves, and also to fire and inflation. ‘Many people have gone to bed rich and woken up poor.’ (Stott) ‘The rich farmer in our Lord’s parable (Lk 12:13-21) thought that his wealth meant security, when really it was an evidence of insecurity. He was not really trusting God. Riches are uncertain, not only in their value (which changes constantly), but also in their durability. Thieves can steal wealth, investments can drop in value, and the ravages of time can ruin houses and cars. If God gives us wealth, we should trust him, the Giver, and not the gifts.’ (Wiersbe)

God, who richly provides us with everything for our enjoyment – ‘We are not to exchange materialism for asceticism. On the contrary, God is a generous Creator, who wants us to appreciate the good gifts of creation. If we consider it right to adopt an economic lifestyle lower than we could command, it will be out of solidarity with the poor, and not because we judge the possession of material things to be wrong in itself.’ (Stott)

Creation was at first very good, Gen 1:31. Even now that there is sin in the world, the material creation is still good in God’s sight and should be seen as good by us. It is a false asceticism which sees the use and enjoyment of the material creation as wrong, 1 Tim 4:1-5. Though the created order can be used in selfish or even idolatrous ways, we must not let the danger of abuse keep us from a positive, thankful, joyful use of it, 1 Tim 6:17. Yet we must remember that all the things of this world are temporary. We are to set our hopes on God, Ps 62:10 1 Ti 6:17; and on his kingdom, Col 3:1-4 Heb 12:28 1 Pet 1:4.

‘The two dangers, then, to which the rich are exposed are a false pride (looking down on people less fortunate than themselves) and a false security (trusting in the gift instead of the Giver). In this way wealth can spoil life’s two paramount relationships, causing us to forget God and despise our neighbour. (Stott)

Now, v18f, comes some positive instruction for the Christian rich.

Rich in good deeds – ‘The New Testament views Christian obedience as the practice of “good deeds” (works). Christians are to be “rich in good deeds” (1 Ti 6:18; cf. Mt 5:16 Eph 2:10 2 Ti 3:17 Tit 2:7,14 3:8,14). A good deed is one done (a) according to the right standard (God’s revealed will, i.e., his moral law); (b) from a right motive (the love to God and others that marks the regenerate heart); (c) with a right purpose (pleasing and glorifying God, honoring Christ, advancing his kingdom, and benefiting one’s neighbor).’ (Packer, Concise Theology) See Mt 23:3n

Those who are rich in this world are to be commanded to be rich in good deeds. Wealth can make people lazy. Since they already have everything they need, they do not have to exert themselves or work for a living. They can easily become ‘the idle rich’. They are therefore to be urged to use their wealth to relieve want and to promote good causes.

Generous – cf. 1 Jn 3:17. ‘Since God is such a generous giver, his people should be generous too, not only in imitation of his generosity, but also because of the colossal needs of the world around us. Many Christian enterprises are hampered for lack of funds. And all the time our conscience nags us as we remember the one fifth of the world’s population who are destitute.’ (Stott)

‘According to the Charities Aid Foundation (CAF), in 2004 only 23% of people in the UK gave regularly to charity. Overall, the average UK household gives £1.70 per week. This compares to £5 spent on tobacco, £6 on alcohol and £30 on eating out, and represents a fall of 25% as a proportion of GDP over the last decade.’ (Stott, Issues Facing Christians Today, 4th ed. p315.

‘Looking over both the paragraphs about money, the apostle’s balanced wisdom becomes apparent. Against materialism (an obsession with material possession) he sets simplicity of lifestyle. Against asceticism (the repudiation of the material order) he sets gratitude for God’s creation. Against covetousness (the lust for more possessions) he sets contentment with what we have. Against selfishness (the accumulation of goods for ourselves) he sets generosity in imitation of God. Simplicity, gratitude, contentment and generosity constitute a healthy quadrilateral of Christian living.’ (Stott)

Conclusion, 20-21

6:20 O Timothy, protect what has been entrusted to you. Avoid the profane chatter and absurdities of so-called “knowledge.” 6:21 By professing it, some have strayed from the faith. Grace be with you all.

Paul may have written these closing lines with his own hand, cf. 2 Th 3:17. In closing this letter, Paul thinks again of the false teachers and their false teaching, who have been in the back of his mind throughout. Positively, Timothy is to guard that which has been entrusted to him. Negatively, he must turn away from pointless arguments.

Timothy – The name means ‘honouring God’, and it may be that Paul has this meaning in mind as he pens these words.

Guard what has been entrusted to your care – Paratheke was a legal term which referred to money or valuables deposited with someone for safe keeping. The Christian faith is something that we have received from our forefathers, and must pass on faithfully to our children. There is much talk these days about different Christian ‘traditions’: but there is only one tradition worth having, and that is the gospel. Timothy is to guard the deposit, so that he can pass it on without denial, dilution or distortion.

‘What is a deposit? It is something that is accredited to thee, not invented by thee; something that thou hast received, not that thou hast thought out; a result not of begius but of instruction; not of personal ownership but of public tradition; a matter brought to thee, not produced by thee, with respect to which thou art bound to be not an author but a custodian, not an originator but a bearer, not a leader but a follower.’ (Vincent of Lerins, 5th cent.)

‘God had committed the truth to Paul, (1 Ti 1:11) and Paul had committed it to Timothy. It was Timothy’s responsibility to guard the deposit and then pass it along to others who would, in turn, continue to pass it on. (2 Ti 2:2) This is God’s way of protecting the truth and spreading it around the world. We are stewards of the doctrines of the faith, and God expects us to be faithful in sharing his Good News.’ (Wiersbe)

There are some truths that are permanent, and must not, and cannot, be modified to suit the prevailing tide of opinion. Paul’s method in this letter is not to systematically refute the false teachings to which he refers, but to urge Timothy to safeguard what he already is convinced of.

The opposing ideas – Gk. ‘antithesis’. ‘The scholastics in the later days used to argue about questions like: “How many angels can stand on the point of a needle?” The Jewish Rabbis would argue about hair-splitting points of the law for hours and days and even years. The Greeks were the same, only in a still more serious way. There was a school of Greek philosophers, and a very influential school it was, called the Academics. The Academics held that in the case of everything in the realm of human thought, you could by logical argument arrive at precisely opposite conclusions. They therefore concluded that there is no such thing as absolute truth; that always there were two hypotheses of equal weight. They went on to argue that, this being so, the wise man will never make up his mind about anything but will hold himself for ever in a state of suspended judgment. The effect was of course to paralyse all action and to reduce men to complete uncertainty. So Timothy is told: “Don’t waste your time in subtle arguments; don’t waste your time in ‘dialectical fencing.’ Don’t be too clever to be wise. Listen rather to the unequivocal voice of God than to the subtle disputations of over-clever minds.”‘ (DSB)

What is falsely called knowledge – The word gnosis is used here. Paul may be referring to some kind of incipient gnosticism. ‘Paul is attacking theosophical and religious tendencies that developed into Gnosticism in the second century A.D. Teachers of these beliefs and practices told believers to see their Christian commitment as a somewhat confused first step along the road to “knowledge,” and urged them to take more steps along that road. But these teachers viewed the material order as worthless and the body as a prison for the soul, and they treated illumination as the complete answer to human spiritual need. They denied that sin was any part of the problem, and the “knowledge” they offered had to do only with spells, celestial passwords, and disciplines of mysticism and detachment. They reclassified Jesus as a supernatural teacher who had looked human, though he was not; the Incarnation and the Atonement they denied, and replaced Christ’s call to a life of holy love with either prescriptions for asceticism or permission for licentiousness. Paul’s letters to Timothy; (1 Tim 1:3-4; 4:1-7; 6:20-21; 2 Tim 3:1-9) Jude 4,8-19; 2Pe 2; and John’s first two letters (1 Jn 1:5-10; 2:9-11,18-29; 3:7-10; 4:1-6; 5:1-12; 2 Jn 7-11) are explicitly opposing beliefs and practices that would later emerge as Gnosticism.’ (J.I. Packer, Concise Theology)

Wandered from the faith – the expression was used of missing the target in archery, and so refers to a swerving or deviation from the truth.

Grace be with you – The ‘you’ is plural, indicating that throughout this letter, Paul has been looking beyond Timothy to the congregations he is serving. Mounce (WBC) considers various explanations, but is clearly sympathetic to the idea that ‘although Paul has written to Timothy, he intends the letter to be read to the church as a whole. This has been evident throughout the epistle and explains why much of 1 Timothy is directed not so much toward a trusted and informed coworker as to the troublesome Ephesian church.’ Fee says that ‘this final plural you is certain evidence that Paul intended the letter to be read aloud in the church(es).’ The letter is personal, but not private.

In all the warnings, encouragements, and instructions with which this letter has been filled, Timothy and his congregation will need to lean and rely on the grace of God, and so reference to this begins, 1 Tim 1:2, and ends the epistle.