This book has proved to be a storehouse of memorable quotations:-

- Vanity of vanities! All is vanity. (Eccl 1:2, ESV)

- There is nothing new under the sun, (Eccl 1:9)

- There is a time for everything, and a season for every activity under heaven, (Eccl 3:1, NIV)

- A cord of three strands is not quickly broken, (Eccl 4:12)

- Cast your bread upon the waters, for after many days you will find it again, (Eccl 11:1)

- Remember your Creator in the days of your youth, (Eccl 12:1)

- Of making many books there is no end. (Eccl 12:12)

And yet Ecclesiastes remains a ‘closed book’ to many, and a mystery to many others.

Provan confesses: ‘It is best to be frank from the outset: Ecclesiastes is a difficult book.’

‘The Book of Ecclesiastes has exercised the Church of God in no uncommon degree. Many learned men have not hesitated to number it among the most difficult Books in the Sacred Canon.’ (Charles Bridges)

‘Ecclesiastes is one of the most puzzling books of the Bible. Its apparently unorthodox statements and extreme pessimism caused its inclusion in the canon of Scripture to be questioned.’ (J. Stafford Wright, EBC)

‘A deeply enigmatic but tremendously compelling book.’ (Longman, DOT:WPW)

Approaches to interpretation

Interpretations that ascribe an essentially negative message.

Some understand Ecclesiastes to be an apologetic or evangelistic tract.

In this view, the author wishes to show the reader the meaningless of life without God.

Eaton: ‘Sometimes the Preacher is thought to present his pessimism for an evangelistic purpose. Since Nicolas de Lyra (c. 1270–1349) Christian orthodoxy has generally held that his purpose was to lift the heart to heavenly things by showing the futility of the world. This was the view of many Reformers and Puritans and their successors (Whitaker, Pemble, Cocceius, the ‘Dutch Annotations’, John Trapp, Matthew Poole, Matthew Henry). C. Bridges represents this tradition: ‘We are permitted to taste the bitter wormwood of earthly streams, in order that, standing by the heavenly fountain, we may point our fellow sinners to the world of vanity we have left, and to the surpassing glory and delights of the world we have newly found.’ John Wesley held a similar view; and this approach has retained its followers in more recent times, most notably E. W. Hengstenberg.’

Eaton notes that ‘if critical orthodoxy has effectively deleted orthodox elements within Ecclesiastes, traditional orthodoxy has at times just as effectively ignored, played down or allegorized its pessimism.

For Eaton, ‘It is an essay in apologetics. It defends the life of faith in a generous God by pointing to the grimness of the alternative.’

Kidner quotes G.S. Hendry with approval: ‘Qoheleth writes from concealed premises, and his book is in reality a major work of apologetic.… Its apparent worldliness is dictated by its aim: Qoheleth is addressing the general public whose view is bounded by the horizons of this world; he meets them on their own ground, and proceeds to convict them of its inherent vanity. This is further borne out by his characteristic expression “under the sun”, by which he describes what the NT calls “the world”.… His book is in fact a critique of secularism and of secularized religion.’

Matthew Henry viewed Ecclesiastes as a penitential sermon. According to this interpretation, the book of Ecclesiastes is written by someone at the end of his life who wants to express regret and repentance over his old way of life. It is, accordingly rather like a penitential psalm. ‘It is a recantation-sermon, in which the preacher sadly laments his own folly and mistake…’ It is a It is a warning to backsliders and to the unconverted, a ‘practical profitable sermon. Solomon, being brought to repentance, resolves, like his father, to teach transgressors God’s way.’

Tremper Longman understands Ecclesiastes to be a picture of a world without God. The world without God is meaningless, and the author has ‘has rightly described the horror of a world under the curse and apart from God.’

Longman writes: ‘The book points us to Jesus Christ, who redeems us from this vanity and meaninglessness. Simply stated, Qohelet’s message is this: “Life is hard and then you die.” He has tried to find the meaning of life in wisdom, pleasure, work, wealth, status, and relationships and has come up empty.’

Longman, along with others, hears two voices in the book: Qohelet, and the ‘frame narrator’. The first describes life ‘under the son’, where the is no meaning in, and no life beyond, death; where injustice is rampant; and where one has no idea about God’s timescale. The speaker at the beginning and end of the book on the other hand, points to a better life, ‘above the sun’ (as it were). ‘The second wise man tells his son to establish a right relationship with God (“Fear God”) and maintain that relationship by obeying his commands and living life in the light of the future judgment. We might anachronistically say that he speaks of justification, sanctification, and eschatology in a verse and a half.’

Francis Watson, similarly: ‘Nowhere else in Holy Scripture is there so forthrightly set out an alternative vision to that of the gospel, a rival version of the truth… In the light of the gospel, nothing could be more illusory than the consolation of Qoheleth’s celebrated realism.’ (Quoted by Bartholemew)

The contributors to Harper’s Bible Commentary do not, it appears, espouse an orthodox view of biblical inspiration. Freed from this constraint, James L. Crenshaw can find in Ecclesiastes a message of unrelieved pessimism:-

‘What was the essence of Qohelet’s reflection about life? His primary word denies earlier optimistic claims about wisdom’s power to secure one’s existence. Moreover, he observes no discernible principle of order governing the universe, rewarding virtue and punishing evil. The creator is distant and uninvolved, except perhaps in cases of flagrant affront like reneging on religious vows. Death cancels all imagined gains, rendering life on earth absurd. Therefore the best advice is to enjoy one’s wife, together with good food and drink, during youth, for old age and death will soon put an end to this relative good. In short, Qohelet examined all of life and discovered no absolute good that would survive death. Profit is thus the measure of life for him. He then proceeded to report this discovery—that there was no profit—and to counsel young men in the light of this stark reality. In sum, Qohelet bears witness to an intellectual crisis in ancient Israel, at least in the circles he taught in.’

There are echoes here of Macbeth:-

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing. (act 5, scene 5)

It would seem that Enns, in his recent commentary, believes Ecclesiastes to be the musings of one who is both a rebellious cynic and a doubting believer. They are analogous to the thoughts of Job’s friends – well-meaning but confused. Enns’ commitment to a certain kind of incarnational model of Scripture (in which the divine element is made subservient to the human element), relieves him of the responsibility of finding consistency either within the book or between it and the rest of Scripture. See this review by Meredith M. Kline.

According to Longman, the bulk of Ecclesiastes (i.e. excepting Eccl 12:8-14) is a work of cynicism that stands in contrast to, and it corrected by, the message of Scripture as a whole. In this view, the teaching of Ecclesiastes is like that of Job’s friends: recorded only to be finally shown as inadequate. The book is intended by the person who put it together as a warning, a teaching devise on ‘how not to do it’.

Then again, some think that Ecclesiastes offers a foil to the more positive teaching of Proverbs. If, for example, Proverbs teaches that the righteous prosper, then Ecclesiastes acknowledges that there are exceptions to this rule. Ecclesiastes (and Job) bring the general wisdom into everyday life, with its dangers, challenges and pitfalls.

Elizabeth Huwiler appears to take a similar view, if less committed to the idea of unity within the biblical revelation. For Huwiler, Ecclesiastes gives a legitimate minority view amongst the Scriptures:-

‘Ecclesiastes stands in contrast to most of the canon. There are no great stories of God’s presence in the people’s midst. Its assumptions about the fate of the just and the unjust, the wise and the fool, are certainly different from those expressed elsewhere in the OT. It is precisely that distinctiveness, however, that exemplifies the value of having a biblical canon: a collection of sacred texts rather than a single book. Qohelet affirms the concept of a time for everything. If one accepts that claim, surely there is a time for not only the ancestral stories of Genesis, the holy songs of the Psalms, and the bold proclamation of the prophets, but also the relentless questioning of Qohelet.’

Greidanus views Ecclesiastes as standing in contrast to the message of Christ. The teaching of Eccle 11:7-12:8, he says, is that death ends everything. But this contrasts sharply with 1 Cor 15, with its message of victory over death. The verdict of Ecclesiastes, that ‘all is vanity’ is reversed by Paul, who says that ‘in the Lord your labour is not in vain’. While there is much that is helpful in Greidanus’ approach, it neglects the ‘not yet’ realities of living in this fallen world and of the remaining taints of our own fallenness.

Edward M. Curtis cites Bruegemann’s approach to the Psalms, which he describes as one of ‘orientation, disorientation, reorientation’. If we take a similar approach to Ecclesiastes, then the Qohelet is leading us to question our present understanding of God’s ways in this world (our present orientation) by drawing attention to the disconnects that seem to occur between how things should be (given an all-powerful and all-loving God) and how things really are (disorientation). He pushes us towards a new understanding, even though he rarely contributes to this reorientation himself. But that new understanding will not conclude that God is either weak or capricious, although it will acknowledge the mystery of God, who nevertheless has given us grounds to trust him, even when we cannot fully understand him.

Elsewhere in the OT, God’s people are taught to meditate upon God’s works in creation and in history as grounds for trusting him. Ecclesiastes, precisely because it does not discourse upon these, ask questions about whether we can flourish in this fallen world or are resigned to a life of fear and frustration. Curtis writes:-

‘Qoheleth makes it clear that life rarely gives unambiguous evidence that God is in control, or that God cares about us, or that his governance of human affairs is beneficent, just, and kind. That knowledge must come from God’s self-revelation and must be embraced by faith. It can be substantiated by experience as people live in the fear of the Lord, experience his provision and grace, and grow into a more intimate relationship with him. As the rest of biblical revelation makes clear, such knowledge, informed by Scripture, can penetrate to the depths of a person’s soul and provide a basis for hope and confidence in a world characterized by the uncertainties, inequities, and irresolvable conundrums seen by this Old Testament sage.’

A positive message?

How to live faithfully in a fallen world

A number of commentators, including J. Stafford Wright, Philip Eveson, Fredericks, and Walter Kaiser, see an essentially positive message in Ecclesiastes. Nevertheless, they would agree that its teaching, although obviously limited in comparison to what we find in the NT, is consistent with orthodox biblical doctrine.

In a classic essay dating from 1945, J. Stafford Wright noted that ‘the interpretation generally adopted is that here we have the struggles of a thinking man to square his faith with the facts of life. In spite of all the difficulties, he fights his way through to a reverent submission to God. The Book then is valuable, since it shows that even with the lesser light of the Old Testament it was possible for a thinking man to trust God ; how much more is it possible for us with the fuller light of the New Testament!’

Wright also contributed the relevant section in the 1st edition of the Expositor’s Bible Commentary. Here, he repeats his view that the interpretation of the book must take account of its theme, announced in the Prologue (‘Meaningless! Meaningless!…Everything is meaningless!’), and of its conclusion (‘Fear God and keep his commandments, for this is the whole duty of man. For God will bring every deed into judgment, including every hidden thing, whether it is good or evil’).

To develop this view in more detail:-

Who is the preacher?

The Heb. term is ‘Qoheleth’.

Eveson notes: ‘It is interesting that in the account of the dedication of the Temple, both the verb ‘to assemble’ and/or the noun ‘assembly or congregation’ occur at the beginning of each key moment: when the ark was brought into the newly built temple (1 Kings 8:1-13; see verses 1-2); when Solomon made his great speech (1 Kings 8:14-21; see v14); when he offered his powerful prayer (1 Kings 8:22-53; see v22); when he blessed the people (1 Kings 8:54-61; see v55); and then after he offered sacrifice in the summing up there is a reference to the ‘great assembly’ (1 Kings 8:62-66; see v65).’

Clearly, says Eveson, this was something very significant about Solomon’s ‘gathering’ of Israel at this important time. Now, in Ecclesiastes, the people of God are called to gather and listen to this Solomonic wisdom.

Who are the people addressed?

Eveson writes: ‘Qoheleth is speaking to an audience of Israelite men and women who have been taught from the book of the Law that God is involved in his world, that he will prosper the righteous and punish the wicked. But time and again he forces his audience to see that life in this world is far from being simplistic and to remember other items taught in the Law of Moses that tend to be forgotten especially when life is treating them well. He brings people down to earth by reminding us that we live in a topsy-turvy world. The world is not what it ought to be.’

Too often (says Eveson), Ecclesiastes is assumed to teach the pointlessness of life without God. But, rather, it is ‘struggling with the problem of understanding the world from the vantage point of one who is a person of faith. It is precisely because he is looking at life as a godly believer that he is all too well aware of the vanity of this world. It is a place of hardship, of toil, misery and death and this is true not only for the wicked but for the righteous. Life ‘under the sun’ is full of frustrations and troubles. The Preacher is impressing upon us that even with God life in this world is vanity.’

‘This book therefore encourages the people of faith to Spring understand that life in this present world will always be full of trouble, and yet to accept whatever joys we do have as gifts from God, and to continue to be wise by fearing God and keeping his commandments remembering there is an eschatological judgement when God will put everything to rights.’

‘Vanity’

‘Vanity’ (AV). ‘Useless’ (GNB). ‘Transient’ (Fredericks). ‘Absurd’ (Fox). ‘Meaningless’ (Longman). ‘Enigmatic’ (Bartholomew). ‘Incongruous’ (Kline). ‘Everything is a breath’ (Provan)

‘As a consideration of the whole book reveals, the emphasis lies on the passing nature of existence and on its elusiveness and resistance to intellectual and physical human control.’ (Provan)

One’s interpretative stance depends much on how one understands the oft-repeated word ‘hebel‘. ‘Its literal sense is “vapor,” which leads to metaphorical uses such as “ephemeral” (Ps 144:4), “vain,” “worthless,” “inconsequential” and the like. In Ecclesiastes, however, these meanings rarely fit. Qohelet’s main contention is not that life is ephemeral or worthless; rather, his cause of such distress is that there is no payoff in what one does. None of our activities result in any sort of ultimate benefit. Hence, a more apt translation of hebel may be, as Fox argues, “absurd.” Life as we experience it is “an affront to reason” (Fox 1999, 31; see also Christianson, 83–88). And what sorts of things are absurd? Things such as pleasure, wealth, labor, justice, wisdom—or, to use the summative word of the frame narrator, “everything” (kōl).’ (Enns, DOT:WPW, my emphasis)

‘D. Fredericks (1993)…argues against the interpretive consensus that hebel should be translated consistently as “transient” rather than “meaningless” (Longman), “absurd” (Fox) or “enigmatic” (Bartholomew). Although there are significant differences between the latter three positions, they are all within the same semantic range in contrast to Fredericks’s suggestion. To have Qohelet proclaim that everything is “transient” is another attempt to turn him into a consistently orthodox thinker and blunt the radical edge of his message.’ (Longman, DOT:WPW)

The word translated ‘vanity’ is, writes Eveson, less about modern ideas of ‘meaninglessness’ and more about ‘transience’, or perhaps even ‘fallenness’. Although this world, as created by God, is a beautiful place (Eccle 3:11), and God has given us many good things to enjoy in it (e.g. Eccle 9:9), the burden is on the effects of the Fall – toil, pain and death. This is reflected in the oft-repeated phrase ‘under the sun’ as descriptive of life – both the godly and the ungodly – in this fallen world.

We are all subject to a life of toil and pain – a life that ends in death. The spectre of death looms over almost every chapter of the book.

Ecclesiastes challenges those who refuse to face up to the reality and inevitability of death. It also challenges ‘health and wealth’ merchants, with their offer of unlimited prosperity in this life.

Ecclesiastes teaches us not to put our faith in the things of this life, and not to become too comfortable in this present, passing world. Its message relieves us from not becoming too disappointed when things go wrong, when things don’t turn out as we hoped or expected, when people let us down.

This teaching is not unique in the Bible. See 2 Sam 14:14; Job 7:7,9,16; Psa 39:4-6; 90:12; 144:3f; Isa 40:6. See also James 4:14 (note James’ words about the fleetingness and uncertainty of life).

Stafford Wright comments on the refrain according to which everything is ‘vanity’: ‘It is sometimes said that Ecclesiastes is never quoted in the New Testament. But surely Paul has this verse in mind when he says in Romans 8:20, ” The creation was subjected to vanity “, and in the context he includes us Christians in the whole creation. In other words whatever may be the precise meaning of Koheleth’s sentiment, there is a general agreement between him and Paul that everything is subject to vanity.’

The same writer points to the book’s conclusion: ‘”This is the end of the matter; all hath been heard; fear God, and keep his commandments; for this is the whole duty of man. For God shall bring every work into judgment, with every hidden thing, whether it be good or whether it be evil ” (Eccle 12:I 3, 14 ). This conclusion is so orthodox that we hardly need any parallel quotations to support it, but we may notice the statement of Christ in Matt. 9:17, ” If thou wouldest enter into life, keep the commandments”, and that of Paul in 1 Cor 3:13, ” The fire shall prove each man’s work of what sort it is “.’

Wright argues that the contents of the book must be interpreted in the light of these two key factors – the repeated refrain of ‘vanity’, and the conclusion which speaks of ‘the whole duty of man’.

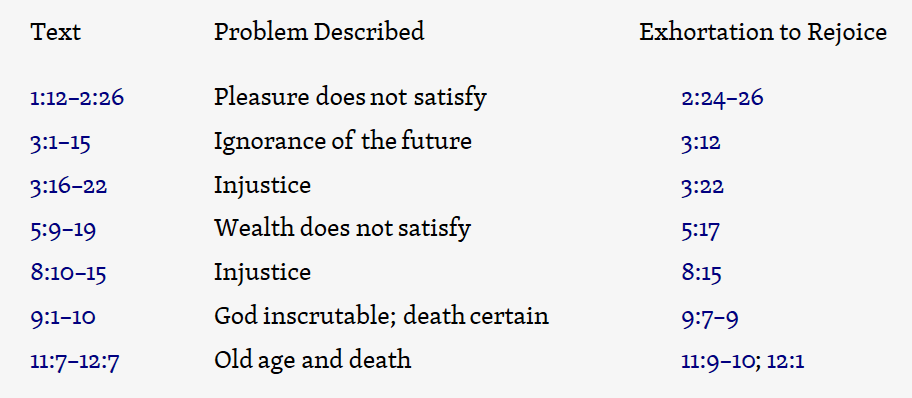

Schulz (NDBT) also takes an essentially positive view of the book’s overall message: ‘The author frames his discourse with his basic thesis: everything is utterly ‘temporary’ (Heb. heḇel, Eccle 1:2; 12:8, a keyword occurring 38 times in Eccles.; see D. C. Fredericks, who argues that the word’s basic meaning is ‘transient’ rather than ‘vain’ [see vanity] or ‘senseless’). He sets out to analyse and assess the activities of life ‘under the sun’ (‘sun’ occurs 33 times in Eccles.) in order to discover what has lasting value (‘profit’, Heb. yiṯrôn, 15 times in Eccles.) in such a world (Eccle 1:3–11, especially v. 3). He considers human achievements and wisdom (Eccle 1:12–2:26), time and eternity (Eccle 3:1–22), social interactions (Eccle 4:1–16), and wealth (Eccle 5:10–6:9, following a brief warning against wrong attitudes towards God and government in 5:1–9; see Poor, poverty). As a result of his investigation, he comes to understand: that ‘bad’ days can bring about good (Eccle 6:10–7:14); that ‘righteousness’ and wisdom can offer only limited protection in this world (7:15–29); that one must submit to the government despite its injustice (Eccle 8:1–17); that, in the light of death, one must fully use one’s opportunities (Eccle 9:1–12); and that one should embrace wisdom and avoid folly (Eccle 9:13–10:20). This leads to his final charge to be bold (Eccle 11:1–6), joyful (Eccle 11:7–10) and reverent (Eccle 12:1–7) while there is still time.’

Ecclesiastes and the gospel of Christ

It was into the fallen world that Christ came, experiencing toil, pain and death. Furthermore:-

‘Furthermore, he experienced the ultimate curse, the second death, God-forsakenness, with no mitigating blessing. But by suffering that awesome curse and death he has broken the curse, brought about the death of death and the end of all pain, sorrow and crying. On account of God’s judgement at the cross and the vindication of Jesus in his resurrection, death has been abolished and life and immortality have been brought to light.’ (Eveson)

Our Lord’s resurrection is the first-fruits of the regeneration of all things, and as believers we begin to experience the benefits of the new creation hear and now. But we are living in the overlap of ages, with our present bodily existence still subject to decay and death even as wait look for the new heaven and the new earth, the home of righteousness. Whereas much biblical teaching emphasises our membership of the New Order, Ecclesiastes would have us face up to the realities of living in the Old Order. Whereas the New Testament offers us a wonderful vision of glory beyond death, Ecclesiastes makes us yearn for that glory precisely because it would have us face up to the grim reality of mortality itself.

As Eveson puts it:-

‘We Christians still experience the frustrations of a world under the curse. Christian women still suffer labour pains in bringing children into the world. Along with the rest of humanity, there are Christians who

become bodily and mentally ill, who suffer Altzheimer’s [sic] disease. Furthermore, we all die. It is tragic to see fine handsome intelligent Christian men and beautiful bright Christian ladies full of energy and drive, who achieve great success and bring great benefits to society, being struck down in the prime of life with some cancerous disease or reduced in old age to wizened old men and women unable to think or do anything for themselves but to lie in a nursing home until death takes them.’

In Rom 8:18-24, Paul teaches that creation was subject to vanity (same word as used in LXX text of Ecclesiastes) and therefore groans in its longing to be set free from its bondage to decay. And we, as believers, groan along with the rest of creation, as we wait for the day of redemption.

While facing up to these realities, the preacher will want to remind his hearers that this old, fallen world is passing away. We are in it, but we no longer belong to it. Let us thank God for this world, and all the blessings he provides for us in it, while never becoming too comfortable in it.

Let’s be realists. ‘At a time when Christians, never mind non-Christians, are afraid to talk about death and to face up to the real world where there is so much unhappiness, distress and cruelty, the Preacher forces us to reckon with the brevity and uncertainty of life and all the other effects of the Fall. We are not allowed to forget that Christians groan with the rest of creation.’ (Eveson)

The Preacher will not allow us to be escapists, turning our backs on the present world while we wait for the world to come. In fact, he calls us to turn away from any contemplation of the future life and face up to the duties, responsibilities, privileges and joys of this present life: transient, troubled and tainted as it certainly is.

But let’s also be full of hope. We look forward to the day when God will put all things to rights (Eccle 12:14). And that vision is wonderfully amplified and clarified in the NT. We long for the day when God will ‘wipe every tear from their eyes. Death will be no more; mourning and crying and pain will be no more, for the first things have passed away … Nothing of the curse will be found there any more’ (Revelation 21:4; 22:3).

Murphy quotes these striking words from Bonhoeffer: ‘It is only when one loves life and the world so much that without them everything would be gone, that one can believe in the resurrection and a new world.’

Echoes of Genesis 1-11

Kaiser identifies the following:-

Man is to live in companionship (Gen. 1:27; Eccles. 4:9-12; 9:9). Man is given to sin (Gen. 3:1-6; Eccles. 7:29; 8:11; 9:3). Knowledge has God-given limits (Gen. 2:17; Eccles. 8:7; 10:14). Life since the Fall involves tiresome toil (Gen. 3:14-19; Eccles. 1:3; 2:22). Death is inevitable for all mankind (Gen. 3:19, 24; Eccles. 9:4-6; 11:8). Order and regularity of nature are God’s sign of blessing (Gen. 8:21–9:17; Eccles. 3:11-12). Life is a “good” gift from God (Gen. 1:10, 12, 18, 21, 25, 31; Eccles. 2:24, 26; 3:12-13; 5:18).

Kaiser Jr., Walter C. Coping with Change – Ecclesiastes . Christian Focus Publications. Kindle Edition.

Bibliography

My starting point in these notes was this article by Philip Eveson. Unfortunately, Eveson does not provide full references to the works he cites. However, I have been able to track most of them down, and consulted some others too:-

Harper’s Bible Commentary

J. Stafford Wright (Expositor’s Bible Commentary)

Elizabeth Huwiler (UBCS)

Eaton (TOTC)

Edward M. Curtis (TTC)

Provan, Iain. Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs (The NIV Application Commentary). Zondervan. Kindle Edition.

Kaiser